Building literacy skills with phonological awareness: Learning methods suitable for Vietnamese children living in Japan (Part 2)

3. The practice report on the phonological awareness instruction for the children with roots in Vietnam

In order to make sure whether the phonological awareness method can help Vietnamese children build literacy skills, the author carried out an experimental trial which has Vietnamese children extract vowels from the words. The reason the author decided to pay attention to vowels as first step of this method is the lack of significant phonological differences for vowels among the dialects. The details are as follows.

3.1. Object and period

The objects of my attempts are two pupils studying at public elementary schools of Osaka prefecture. First object is T, a third-grade girl. Her parents are from Southern Vietnam. She speaks Vietnamese mainly at home, and her mother takes a positive attitude toward teaching Vietnamese to her 6. The family returned to Vietnam for several weeks this spring. This trip gave her a strong impression so she was able to speak Vietnamese with the author in the class after this trip. She could read and write some letters.

Second object is V, a third-grade girl. Her parents are also from Southern Vietnam. She speaks Japanese mainly at home, but she can hear her parents’ Vietnamese and sometimes speaks Vietnamese too. In the school, she takes the author’s Vietnamese lessons in Japanese and many times she can’t remember even the basic words. About writing and reading, she says “I’ve seen some letters. I practiced to write some letters in the Vietnamese class before, but I don’t remember how to read them.”

The practice was conducted from the end of May to July 2012; each object had five lessons (45 minutes/ lesson)

3.2. Procedure

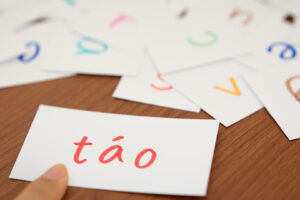

(a) Vocabulary card game

The author prepared 49 picture cards8. The words on the cards were basic words used in everyday life which had open syllables and included all of 14 vowels. The author showed the card and asked them what it was. If they knew the word, they can get the card.

The goal of this activity is collecting the words they know including at least 2, 3 words per vowel. Besides, the important point here is approving their vocabularies so that they can be proud of their own Vietnamese ability.

(Figure 2) Picture cards

(b) Grouping sounds (See sound categorization task in Ball & Blachman 1988, 1991, Bradley & Bryant 1983)

After deciding the cards to use, next step is grouping sounds. The author made children to divide the words into some sound-groups so that the words having a similar sound were in a same group. The author illustrated that they had to divide the words paying attention to the sound in the end part of the word with some examples like “Lá [la:] and nhà [ɲa:] are in a same group, but lá [la:] and gió [jɔ:] are not”.

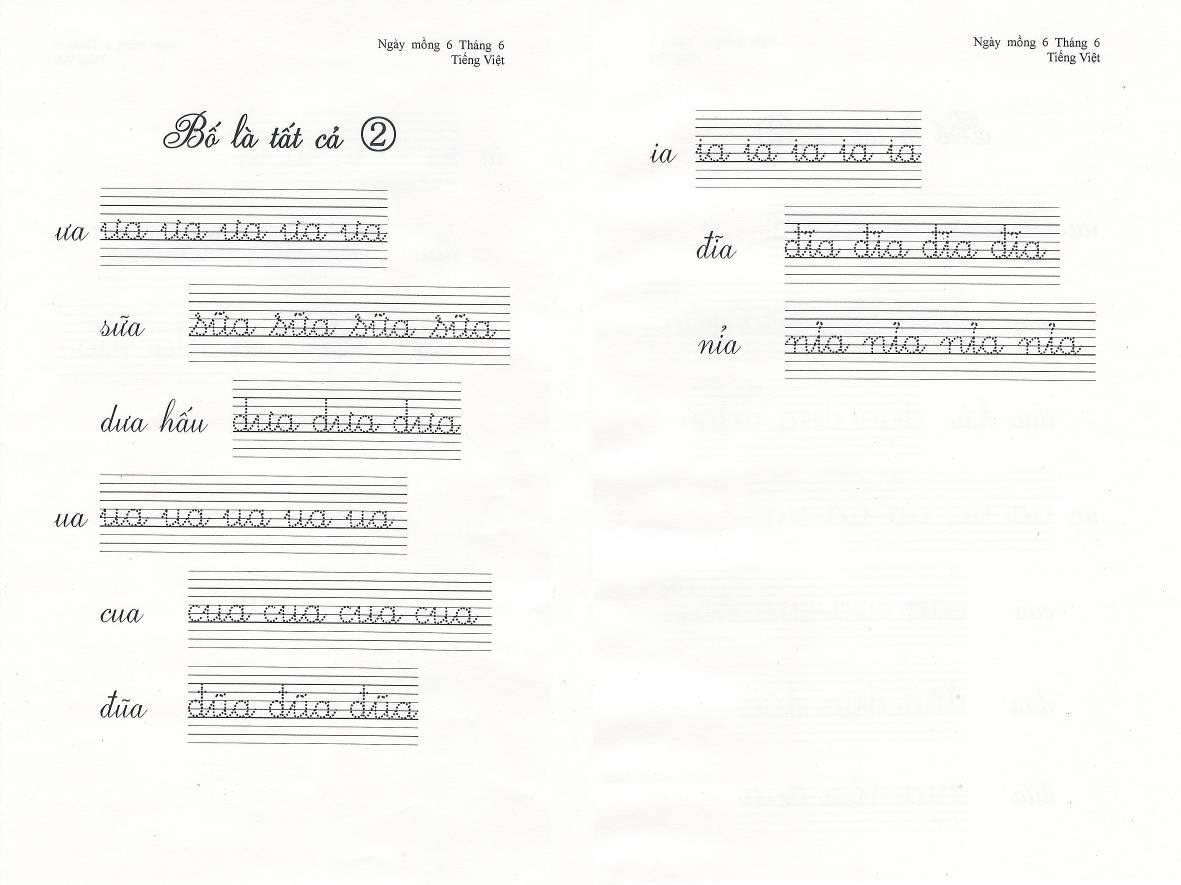

(c) Giving letters for each sound group

The third step is to make the connection between sounds and letters. The author showed them the words in a group again and showed the new card having the letter representing the sound.

After that, the author gave them an assignment to practice writing the letters.

(Figure 3) The assignment

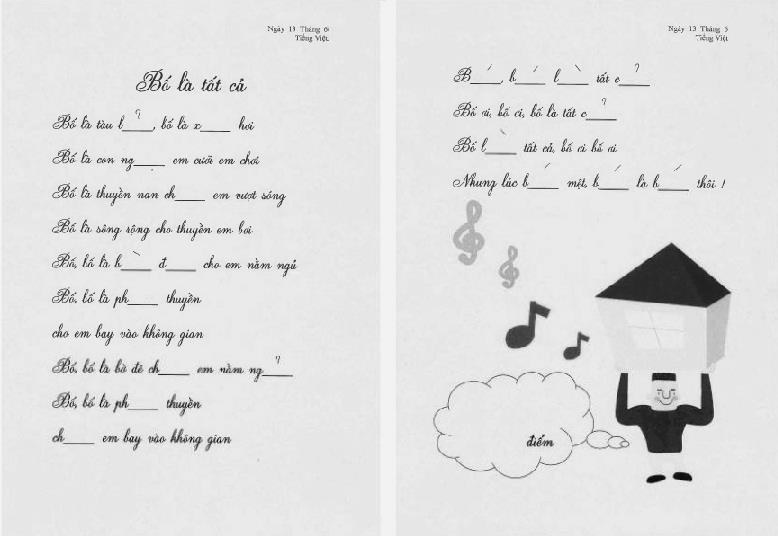

(d) Test

The last step is testing. In addition to the activities in the class above, the author gave them another assignment as homework. The assignment is to sing the song “The father is all (Bố là tất cả)” by heart. Children were given this song’s CD and lyric. They brought them home to have their parents read to them and listen to the CD.

The lyrics were prepared without vowels. The children filled in the blanks.

(Figure 4) Test

3.3. Result

(a) Vocabulary card game

In the case of T:

She enjoyed this game-style activity very much. She knew many Vietnamese words, so her vocabulary could cover all of the vowels. She seemed to be confident of her own vocabulary and she wanted to do the activity like this more. The result is that 45 words can be used to do the phonological awareness activity.

In the case of V:

She also enjoyed the game-style activity, but she didn’t know Vietnamese words very well. When she saw a series of unknown cards, she took negative attitude and said “I don’t know Vietnamese very much.” She couldn’t remember some words just by looking pictures, but was able to answer when the author gave her some contexts as hints.

Ex. về (come back)

V: (looking at the card) I don’t know this word.

The author: What do you do after you finish studying?

V: Về nhà (come back to home).

Ex. trà (tea)

V: (looking at the card) I don’t know how to call tea in Vietnamese.

The author: Have you ever heard your mom say “Con uống trà đi (Drink tea)” ?

V: I have. “uống trà (drink tea)”

She couldn’t remember some words by herself, but could recognize after the author said the words. The author had V remember these words (ghế, nấm, số, chìa khóa, trăm, mưa). She didn’t know the words including vowels ư /ɨ:/ and ia /iə/ which the author prepared so the author looked for her vocabulary with these vowels. Finally the author found 2 words (sư tử, đĩa) and added these 2 cards. She got 28 words to use in the phonological awareness activity.

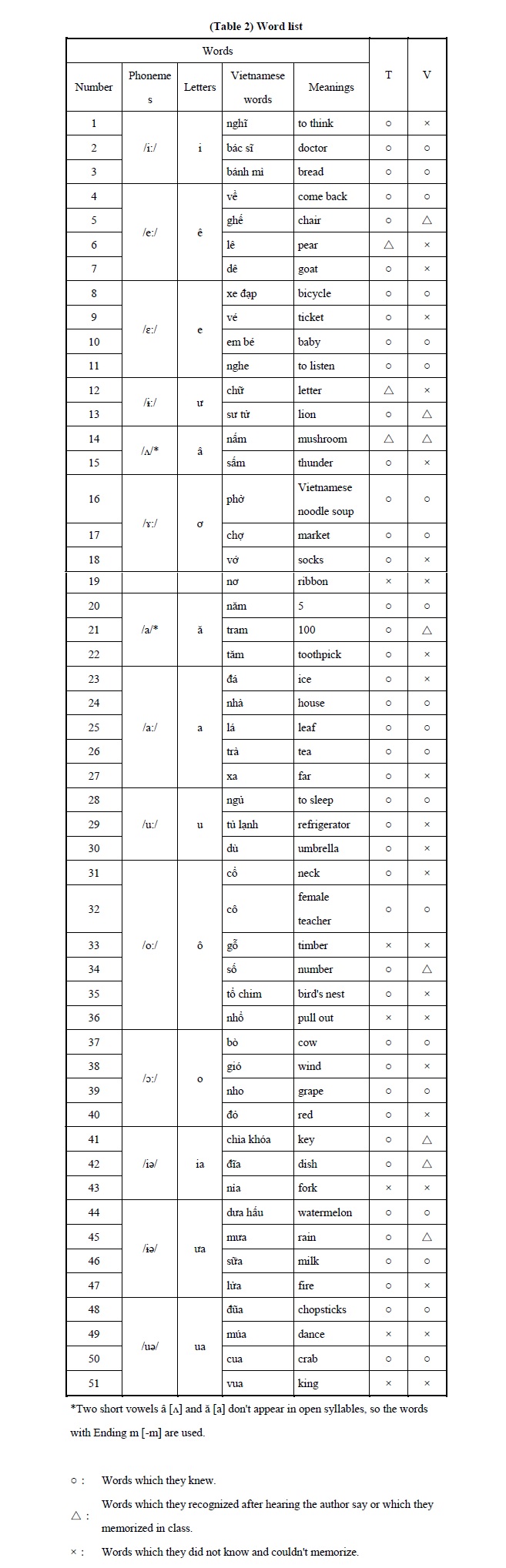

The words which the author selected to use in the phonological awareness training through this activity are below.

(b) Grouping sounds

In the case of T:

When the author showed some examples of grouping such as “Lá [la:] and nhà [ɲa:] have a similar sound, so they are in a same group”, she seemed to get the hang of the exercise. First, the author gave her the picture cards with the two to three vowels. As she became accustomed to grouping, the author gave her cards with more vowels. She tried to group the cards, pronouncing the words one by one.

The results were follows. Roughly speaking, she could divide the cards into sound groups based on the vowels, but she had difficulty in distinguishing some vowels. The vowels ê /e:/ and e /ɛ:/ couldn’t be distinguished and her pronunciation of these two vowels were much the same. The vowels ô /o:/, ơ /ɤ:/ and o /ɔ:/ were also difficult to tell one from the others for her. But, in this case, she could pronounce each vowel correctly. So when the author had her notice the sound in the end part of the word, the shape of her mouth after pronunciation more carefully, she could manage to group them. The vowels u /u:/, ô /o:/ and ua /uə/, they were also hard to distinguish. All these three vowels are pronounced pursing the lips, leaving her slightly confused. The two vowels â /ʌ/ and ă /a/ don’t appear in the open syllables so the author used the words with the ending m/m/. Her pronunciation of two rhymes was much the same. Even when listening to author’s pronunciation, she didn’t recognize the difference. The reason was that she tried to listen to the ending sounds of the words, both of them are m /m/.

She already knew some alphabet, and this knowledge seemed to influence her practice. For example, she couldn’t recognize the difference among three vowels ô /o:/, ơ /ɤ:/ and o /ɔ:/ at first, but she knew the three letters ô, ơ, o, so she thought she had to divide into three groups. Due to alphabet awareness, she didn’t focus only on her pronunciation.

In the case of V:

She also seemed to get the hang of the exercise when the author explained the methodology. First, the author gave her the picture cards with the two to three vowels. As she became accustomed to grouping, the author gave her cards with more vowels. She could do the work focusing on her pronunciation very well. She touched with her hands and looked in a mirror the shape of her lips after pronouncing carefully to confirm her pronunciation. When she couldn’t judge the sounds, she asked the author say the word and watched the shape of the author’s lips.

She also had difficulty in distinguishing some vowels. She sometimes confused two vowels i /i:/ and ia /iə/. When she pronounced the words, she told one sound from the other, but both of two sounds had pronunciation pulling the edges of lips to the sides, so it was a little hard for her to judge. The vowels ê /e:/ and e /ɛ:/ couldn’t be distinguished and her pronunciation of these two vowels were much the same. So are the vowels ô /o:/, ơ /ɤ:/ and o /ɔ:/. Some of the words with these vowels were same, some were distinguished. When she divided the cards with these vowels into group, she asked the author pronounce to judge the sounds. The vowels u /u:/, ô /o:/ and ua /uə/ were also hard to distinguish because these three vowels are similar sounds made with pursed lips. The sounds with rhymes âm /ʌm/ and ăm /am/ were also hard to tell one from the other.

Unlike the case of T, V could focus on the sounds very well. Each time she grouped the cards, she pronounced by herself, touched her lips, looked at the shapes of her lips in the mirror, asked the author pronounce and so on in order to judge what the sound was. Her knowledge of the alphabet didn’t influence her work.

(c) Giving letters for each sound group

After they could group all of the sounds correctly, the author gave the letter cards to the sound groups. When the class had spare time, the author taught how to write letters and had them practice. When no time was available, the author gave them the assignment to practice letter writing at home. The two of them worked hard on the assignment.

(d) Test

On the last day of this experimental trial, the author had them take a letter test. First, the author had them sing the song “The father is all (Bố là tất cả)” to ensure whether they could memorize it well or not. The result was that they could sing the song by heart perfectly. When they took a test, the author prepared the picture cards so that they could use them to compare the sounds.

The results of their tests are as follows.

In the case of T

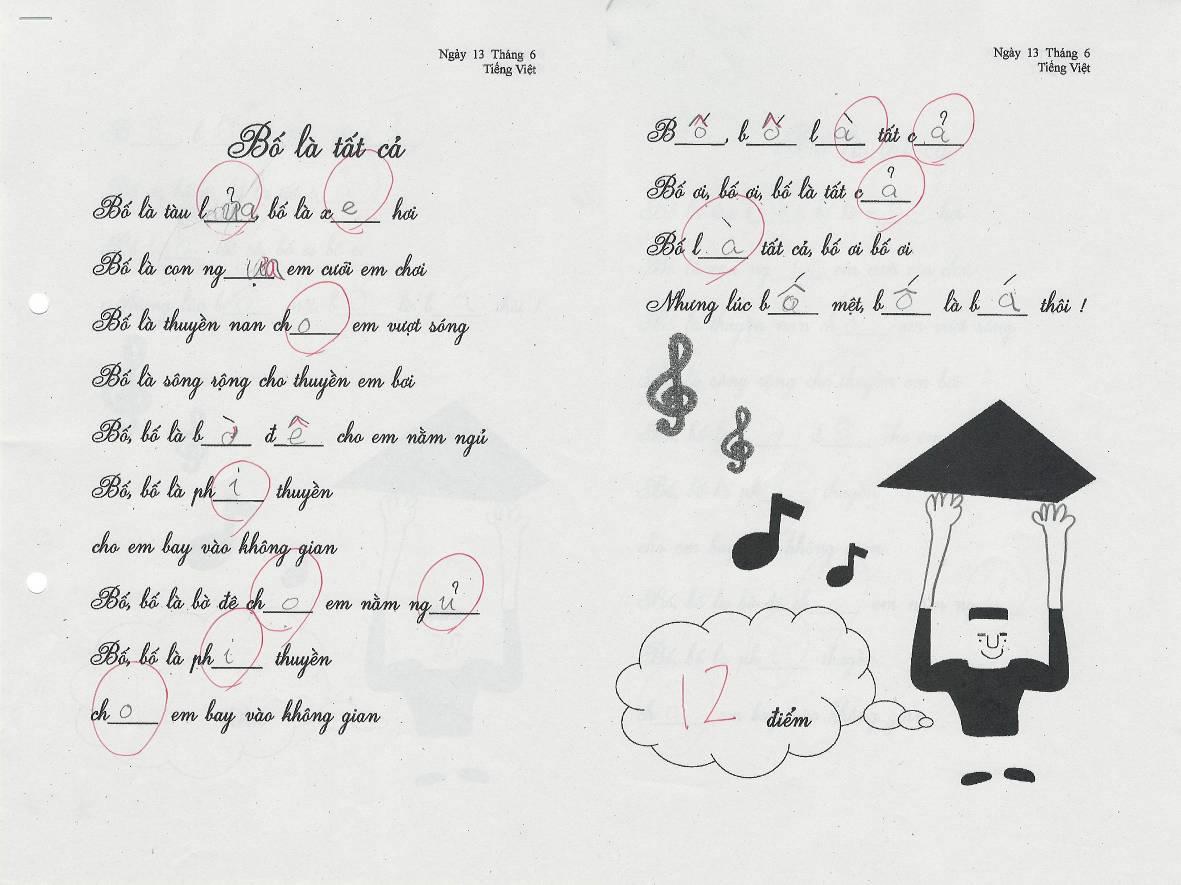

She pointed the syllable one by one singing slowly and confirmed the syllable where she had to fill a blank. When she came to the syllable to fill a blank, she pronounced the word carefully and wrote a letter. Her test is below.

(Figure 5) The test of T

The syllables with ê/ e were filled by e, the syllables with ô/ ơ/ ơ were filled by o. She didn’t distinguish two vowels ê/ e in pronunciation so she couldn’t tell one from other. She pronounced all of three vowels ô/ ơ/ ơ, but she couldn’t recognize the difference among three when she took a test.

In the case of V

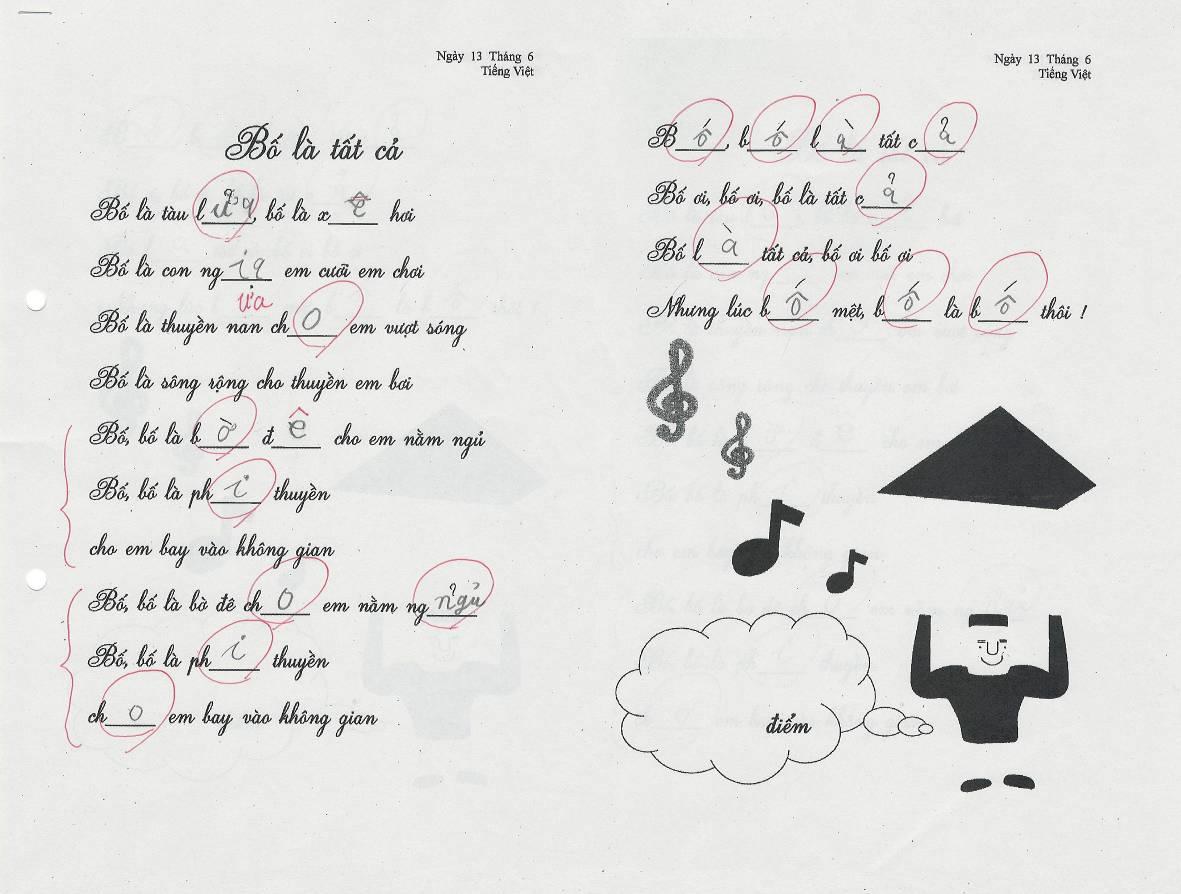

She also pointed the syllable one by one singing slowly and confirmed the syllable where she had to fill a blank. When she came to the syllable to fill a blank, she pronounced the word carefully some times and tried to judge what the sound was. After she pronounced some times, she tried to compare the sound with the sound of the picture cards. She pronounced the sound on the lyric and the sound of the picture card in turn. She answered very carefully. Her test is below.

(Figure 6) The test of V

She also didn’t distinguish two vowels ê/ e in pronunciation so she couldn’t tell one from other. Both of two vowels ê/ e were filled by ê. She filled ia in the syllable with ưa. When she grouped sounds, she didn’t confuse these two vowels.

4. Conclusion

The author has shown her experimental practice instructing literacy skills for Vietnamese children living in Japan. The author used a phonological awareness method for two pupils, who had common characteristics found among Vietnamese children living in Japan, that is, speaking Southern dialect and being born in Japan. The vocabulary that they had already had was used in order to extract vowels, and the letters were connected to each vowel. The result was that they could pay attention to a component of the syllable (vowels) and they became able to roughly distinguish vowels in a short period. The phonological awareness method can be said to help early reading and spelling for Vietnamese children in Japan.

However, there are some problems to solve. The First is about children’s knowledge of letters. As seen in the case of T, it is possible that the knowledge which the children have already had could influence the activities of this method. The second is the influence of Japanese. Both T and V had difficulty in distinguishing the vowels ê/ e and ô/ ơ/ o. That can be caused by Japanese phonological knowledge. Japanese doesn’t distinguish these sounds. It is necessary that we patiently instruct children to concentrate on the sound of Vietnamese.

After they master the vowels, the author will move to the tones, the initials and the endings. The points with the differences between orthography and dialect pronunciations have to be considered carefully, to ensure clear instruction.

After this, the author will continue to improve this phonological awareness method to teach reading and spelling for Vietnamese children in Japan. The author strongly hopes that pupils with roots in Vietnam could maintain Vietnamese language and their identity as a Vietnamese living in Japan.

Reference

Ball, Eileen W., and Benita A. Blachman 1988, “Phoneme Segmentation Training: Effect on Reading Readiness” Annals of Dyslexia, Vol. 38, pp. 208-225 1991, “Does phoneme awareness training inkindergarten make a difference in early word recognition and developmental spelling?” Reading Research Quarterly, vol. 26 (1), pp. 49-66

Ball, Eileen W. 1993 “Assessing Phoneme Awareness”, Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, Volume 24, pp.130-139

Bradley, L. and Bryant, P. 1983. “Categorizing sounds and learning to read: A causal connection” Nature, Vol. 301, pp.419-421.

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology 2011, The guidebook of the acceptance of the foreign students [外国人児童生徒受け入れ の手 引 き ] (http://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/clarinet/002/1304668.htm, accessed on September 11, 2012)

The Ministry of Justice 2012, Statistical charts of registered foreigners [登録外国人統計統計表] (http://www.moj.go.jp/housei/toukei/toukei_ichiran_touroku.html, accessed on September 11, 2012)

AMANO Kiyoshi 1970, “Formation of the act of analyzing phonemic structure of words and its relation to learning Japanese syllabic characters (Kanamoji) [語の音 韻構造の分析行為の形成とかな文字の読みの学習]” Kyoiku Shinrigaku Kenkyu, vol. 18 (2), pp. 76-89

SHIMIZU Masaaki 2007, “From the creation of chữ Nôm characters to the adoption of the Roman alphabet [字喃の創出からローマ字の選択へ]” , Gengo, vol. 36(10), pp.64-71

KAWAKAMI Ikuo 2001, The families crossing the border –The life of people with roots in Vietnam living in Japan- [越境する家族 在日ベトナム系住民の生活 世界] Akashi Shoten

KONDO Mika, SHIMIZU Masaaki 2012, “The activities using picture books at S elementary school [S 小学校における絵本を使用した取り組み]” MAJIMA Junko ed. 2009-2011 Reports of Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, Foundation research (C) [21610010], Osaka University

MAJIMA Jyunko 2009, “On the importance of supports for mother language education for foreign students -from the experience of supports for mother language education in Hyogo prefecture- [外国人児童生徒への母語教育支援の重要 性について‐ 兵庫県の母語教育支援事業に関わって]” Reports on supports for mother language education for newcomer students in 2008, pp.38-43, Hyogo Prefectural Board of Education

TOMITA Kenji ed. 2007, Joyful Vietnamese [Tiếng ViệtVui] Tokkabi kodomokai Hoàng Thị Châu 2004, Vietnamese dialectology [Phương ngữ học tiếng Việt] NXB Đại học Quốc gia Hà Nội.